NISHA IS PARTICULARLY vulnerable to guilt. Anyone can make her feel guilty for something she’s done or not done. In school, her classmates repeatedly ridiculed her for her ‘guilt complex’. In her early twenties, she married a man of her family’s choice because they made her feel guilty for questioning their opinion. Several years into a loveless marriage, she had an affair with a colleague. After it ended, she spent years beating herself up for being an ‘immoral’ woman.

Sounds familiar? Do you know people whose lives have followed a similar trajectory? Or people who are carrying a heavy burden of guilt? Chances are you might because guilt and worry are the two most common forms of distress in many cultures, according to American psychiatrist Dr Wayne W. Dyer.

Wasteful emotions

In his 1976 bestseller Your Erroneous Zones, Dr Dyer terms guilt for what has been done and worry for might be done the two most futile and wasteful of all emotions. “Guilt means that you use up your present moments being immobilised as a result of past behaviour, while worry… keeps you immobilised in the now about something in the future – frequently something over which you have no control,” he writes.

He sees them as opposite ends of the same erroneous zone: while guilt fills up the present with despairing feelings about the past, worry uses up the present in obsessing about the future. “Whether you’re looking backwards or forwards, the result is the same. You’re throwing away the present moment.”

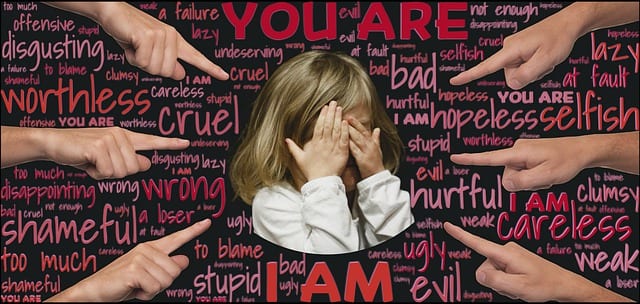

Conspiracy of guilt

Let us take Nisha’s example to understand how the guilt mechanism works. After she hesitated to marry the person of her family’s choice, someone sent out a message that her disobedience had made her a ‘bad’ person. She responded by feeling bad, unwittingly turning herself into a living ‘guilt machine’. From then on, all someone had to do was pour fuel into the machine and it would respond with guilt. “Many of us have been subjected to a conspiracy of guilt in our lifetimes, an uncalculated plot to turn us into veritable guilt machines,” writes Dr Dyer.

The reason why people buy the guilt messages dumped on them is because it is considered ‘bad’ not to feel guilty. “It all has to do with CARING. If you really care about anyone… then you show this concern by feeling guilty about the terrible things you’ve done… It is almost as if you have to demonstrate your neurosis in order to be labeled a caring person,” he says.

Birth of guilt

There are two ways in which guilt becomes a part of a person’s emotional makeup. These are:

(i) Leftover guilt: This is learned in childhood but continued into adulthood as a leftover childish response. It is an emotional reaction triggered by childhood memories. For instance, a child is often given a guilt-producing rap such as “Daddy won’t like you if you do that again”. The implications can produce hurt in an adult too, if s/he disappoints a boss or any figure to whom s/he has given parental status.

(ii) Self-imposed guilt: This is the more troublesome type of guilt, according to Dr Dyer. Here, a person is immobilised by something recent. “This is the guilt imposed on the self when an adult rule or moral code is broken,” he writes. As in Nisha’s case, an individual will long feel bad for cheating on a spouse but the guilt will not change anything.

Conclusion

“You can look at all of your guilt either as reactions to leftover imposed standards in which you are still trying to please an absent authority figure, or as the result of trying to live up to self-imposed standards…,” sums up Dr Dyer.

“In either case, it is stupid and, more important, useless behaviour. You can sit there forever, lamenting about how bad you’ve been, feeling guilty until your death, and not one tiny slice of that guilt will do anything to rectify past behaviour. It’s over! Your guilt is an attempt to change history, to wish that it weren’t so. But history is so and you can’t do anything about it.”

IN OUR NEXT POST: Typical guilt-producing mechanisms; payoffs of choosing guilt, strategies to get rid of guilt.